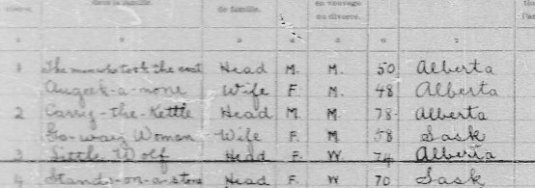

I came across The-Man-Who-Took-The-Coat in the 1906 Prairie Census when I was looking for the Hassans, and I had to know the story behind his name. Did he take a coat as part of a deal? Steal a coat? Bring a coat to someone?

When white men came to the Prairies and parcelled off the land and displaced the people already there, they moved the people of The Man Who Took The Coat and a chief called Long Lodge to an area outside Sintaluta, Saskatchewan and the Assiniboine Reserve was created under Treaty 4. Originally they had wanted the Crown to grant them land near Cypress Hills, which held great spiritual importance because of a terrible massacre that had claimed many of their people.

After a chief signed the treaty, Indian Affairs would give him $25, a silver medal, and a coat. However, they were calling him this before the treaty was signed. Could it be because he intended to sign and take the coat, or for another reason lost to time?

After The Man Who Took The Coat died, his brother, Carry-the-Kettle became Chief of the people who lived on that part of the Assiniboine Reserve, and became known as the Carry The Kettle Nation.

Here is what Deanna Ryder and Doug O’Watch of Carry The Kettle First Nation say about the origins of Carry-the-Kettle’s name:

After the death of Chief Long Lodge in 1884, the two Assiniboine bands were joined and leadership of both bands was assumed by The Man Who Took The Coat until his death in 1906. At this time Carry The Kettle succeeded his brother as Chief.

Doug O’Watch tells us how the Chief recieved his name:

“The indians were camped along a deep coulee. All at once a big enemy of Blackfeet or Bolld came to raid. ‘Come on, ladies, take the belongings to the coulee, stay, we’ll gaurd.’ The men built barricades of wood and stone. The boys played behind the barricade. A little boy goes back to his teepee. His mom took all. She left a kettle. He took it. He tied it around his neck. He played behind the barricade all during the battle that way with the kettle on his back. When the battle was over the men were retelling what had happened. ‘What about that little boy?’ After that he was known as Carry The Kettle.”

There are conflicting dates about The-Man-Who-Took-The-Coat and Carry-The-Kettle. Indian Agency reports from 1877 state that The-Man-Who-Took-The-Coat would have been a young chief, around 22 years old, which matches the age of The-Man-Who-Took-The-Coat in the 1906 census (the same man appears in the 1911 census with his wife). However, the Indian Affairs Annual Report for 1891 says that Chief Jack (The-Man-Who-Took-The-Coat) died that year, and Carry-The-Kettle became chief. Chief Jack’s widow is listed as having returns on crops.

1. The-Man-Who-Took-The-Coat died in 1891, and a different person with the same name appears on later censuses.

2. The-Man-Who-Took-The-Coat declared that “Chief Jack” was dead, Carry-the-Kettle headed the people, and The-Man-Who-Took-The-Coat lived until at least 1911.

Which is the truth?